2003

December 2003

Have a happy Christmas and a transformationalistic New Year!

***

November 2003

***

October 2003

Burslem Dreams 2 Sell is a new website created by local historian Fred Hughes.

***

September 2003

Kenneth McLean of Canada kindly sent me the following:

“Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are in; the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a total mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.”

***

August 2003

On a recent visit to Dunwich I was amused by a road sign with a picture of a large amphibian, either frog or toad, just outside the village. H.P. Lovecraft can be accused of many things but not transformationalism. The same cannot be said of the sign erectors of East Anglia.

***

July 2003

And when they ask me, "What is transformationalistic?" I am stumped. All I know is, I know when something is transformationalistic, but it is not the easiest thing to put into words. For example - again from the Guardian (Review section, 21.6.03) - a new novel by Niall Griffiths, called 'Stump', the review by Toby Litt illustrated by a photograph of a Morris Minor. To me this was transformationalistic - I felt a shiver run down my spine. To explain:

For the past decade I've been writing a series of books set in the fictional city of Stump (a thinly disguised version of Stoke-on-Trent). One coincidence then and not a great one at that, Mr. Griffiths' book does not involve a city called Stump. The Stump in his book is a one-armed man, who lives in Aberystwyth. I have a friend who lives in Aberystwyth. He possesses two arms. In Mr. Griffiths' 'Stump', two hitmen travel from Liverpool to Aberystwyth to kill the one-armed man. Now I have to explain the structure of my sequence of novels set in the city of Stump - after the first one, 'In Stump II', the next three concern a hitman called Doctor Shock. None of this is particularly transformationalistic, merely a series of coincidences. The hitmen in Mr. Griffiths' 'Stump' drive to Aberystwyth in an old Morris Minor. The review in the Guardian, as I said, was accompanied by a photo of an old Morris Minor. My friend in Aberystwyth, he of the two arms, has three Morris Minors. For the past year all of his conversation has revolved around these cars. His obsession is Morris Minors. Mine is the City of Stump. These two obsessions have leaked out somehow and attracted the attention of Mr. Griffiths. This is transformationalistic.

***

June 2003

A strangely transformationalistic passage occurred in an article about the decline of the pottery industry in Stoke-on-Trent which was published in The Guardian on June 11th:

“Fenton may have been cruelly omitted from Bennett's novels, but, curiously enough, Juan Luis Borges set a strange, magical little tale called The Garden of Forking Paths in a "suburb of Fenton". (Incidentally Flaubert, one of Bennett's literary heroes, once mentioned Stoke in a notebook, but infelicitously rendered it Stroke Upon Trend.)”

No doubt this will be dismissed as just another Guardian proofing error, but personally I like to think of Juan Luis Borges beavering away to recreate the work of old blind Jorge, much as Pierre Menard approached ‘Don Quixote’. I imagine him in some crumbling old library in Buenos Aires, but I suppose he could be as close as Stroke Upon Trend.

***

May 2003

A tribute to one of the foremost exponents of Transformationalist cinema, Godfrey Ho, can be found here.

***

April 2003

THE LIBRARY OF THADDEUS TRIPP

by

Dean Hammersley

4. The 48

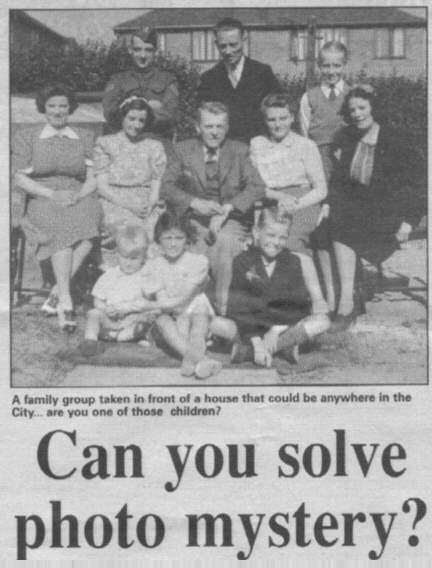

“Have you seen this?” said Thaddeus, tossing me that evening’s edition of the local paper. He pointed to a photograph from the 1950s above the headline, ‘Can You Solve Photo Mystery?’ I read the article. A local man had found a pile of old photographs in his shed and wondered if anyone knew who they belonged to, so the paper printed a few and we were all supposed to take a look and exclaim ‘Why that’s my Uncle Bob!’ Except it wasn’t. But the little lad at the front could have been my cousin, Roy. And the man standing at the back reminded me a bit of Roy’s dad, my Uncle Lew. But that was it, the rest were strangers. Although the more I looked at them, the more familiar they began to seem.

“Nothing to do with me,” I said and threw the paper back at Thaddeus.

“That woman sitting on the left is the spitting image of my Auntie Doris.”

“The little lad’s my cousin Roy, the bloke at the back’s my Uncle Lew.”

“Strange, isn’t it?”

No, it wasn’t strange. It wasn’t Roy and his dad, it just looked like them. Or, to be more specific, the ‘Roy’ and ‘Uncle Lew’ in the shed man’s photo reminded me of the monochrome Roy and Uncle Lew in the old family photos from the 1950s which now held pride of place in a cardboard box in my loft. I knew that if I went and dug one out and compared it to the photo in the paper then all resemblance between ‘Roy’ and Roy would fade away. Not to mention Uncle Lew. Any other evening I would point this out to Thaddeus and the ensuing argument would last us till hometime. But I had spent the afternoon watching cowboy films and so I was in a mellow mood and did not feel like engaging Thaddeus in lively debate. So I just let him run with it and gave him the occasional nod between drags.

“Maybe it’s just that all photographs from this period meld together with the memories of our own family photos so that in the end the people all begin to resemble each other. But it called to mind that peculiar fragment of Manuel Garcia Monteros, ‘The 48’. This is perhaps the strangest of all his works and certainly the one which has provoked the greatest controversy. It begins, ‘There are 48 people in the world.’ After which there follows a list of 48 names. That’s it. Scholars have struggled with it for years. They are not the names of the rich and famous, they are not politicians or businessmen. There are no world leaders, no princes, popes or potentates. Apart from Monteros himself and a relatively obscure jazz musician, there are no other artists on the list. The rest of the names are unremarkable.

It was suggested by Dr. Hans Moeller that ‘The 48’ is a list of the friends of Monteros. Or, to be more precise, those people whom he knew so well, so intimately, that he could attest to their existence. A solipsistic extension, if you will. How many people do any of us really ‘know’? Family, friends, neighbours, but what happens to the man next door when he has finished clipping his hedge and goes back inside his house. Is he still there? How can you be sure? So, Dr. Moeller suggested that we all have a ‘48’, perhaps more, perhaps less, but the actual number of people that we know in the world is relatively small. He wrote a paper on the subject, which he presented to the 1973 Monteros Symposium in Stuttgart. Monteros, of course, did not attend, but he must have been informed of the good doctor’s efforts to dispel the mystery of ‘The 48’, for shortly after, he sent a letter to the organisers of the Symposium, which stated, quite simply, that the name, Hans Moeller, was not included in the list of the 48 people in the world.”

Thaddeus paused for a moment. He glanced at the photograph again, then shook his head. I watched a blizzard of dandruff fall on his shoulders.

“Monteros wrote ‘The 48’ in 1966. My Auntie Doris was not on the list and neither was there a Roy or a Lew. It’s strange how we can be compelled to accept the existence of people through a simple arrangement of light on paper. And what of the others whom we are told exist in the world? The incredible infestations of China and India, the millions who inhabit the great cities of London and New York. We see them on the television screen but what is that? Light on glass.

Some believe that ‘The 48’ is written in code and they have tried to decipher its meaning. Others think that only a mathematician could unravel its secret. Personally, I’ve always thought it best to accept it at face value. Monteros states that there are 48 people in the world and so, there are. His name appears among the 48 but mine does not, and neither does yours, even though we were both ‘in the world’ when the list was compiled. Or so we have been led to believe. In fact, we do not exist.”

***

March 2003

***

January 2003

Among Frederick Hammersley’s few surviving papers is a brief note - undated and unsigned - containing the following words:

“It is high time we embarked upon the third and final stage of our plan.”

No mention is made elsewhere of the other two stages of the Transformationalists’ plan and the details of the third are likewise unknown. Whether it was ever begun, is still in operation or has finished, is anybody’s guess.

***